Conflicts in Somalia continue to cost lives, draw in funding and demand attention from the international community. Somalia has evolved from ‘stateless’ and ‘failed state’ but the high levels of violence and conflict continue their tragic impact on people’s lives. I have worked in and on Somalia since 2013 and there are six characteristics of the conflicts that seem to be counter-intuitive, yet I notice that they occur often. They are not unique to Somalia, but often Somalia seems to demonstrate conflict lessons particularly starkly. This article describes the conflict lessons and their implications for delivering support in Somalia today.

1. There is a conflict equilibrium

Somalia is unstable, but there is a stable instability: balancing the risks and opportunities that could arise if there were a shift to either more conflict or less conflict. Less conflict would mean a reduction of donor funding, more regulation and greater expectations that Somalia should conform to international rules and norms. Greater conflict would be disruptive for business and aid flows. My sense is that this is not a coincidence, but rather a delicate balance between the various interests and power bases – political, business, clan, criminal. A war economy, covering socio-political interests.

That is not to understate the violence or its impact. Tragically, high numbers of civilians are killed in Somalia – 982 between January and September 2018, down on the previous year’s figure of 1,228 civilians killed in the same period. And there have been significant attacks on international community targets.

But, to flip this around, why aren’t there more attacks on the international community in Mogadishu (and elsewhere in Somalia)? For all the security provision, there are numerous ‘soft’ targets for those wishing to disrupt the fragile peace. Of course, attacks take place, but they could be happening a lot more.

2. We are not asking ‘why?’ enough; it isn’t chaos, but we assume it is

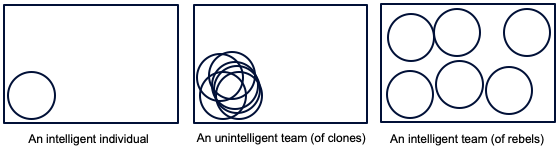

“It’s complete chaos!” – I’ve heard that phrase a lot and it is, perhaps, most common misunderstanding that internationals make about Somalia. Bluntly, it isn’t chaos. There is a system that functions. But it doesn’t function as we expect it to or think it should.

It’s common for people arriving to work in Mogadishu with experience of other conflict-affected countries. We try not to make assumptions but also try to apply what we have learnt from other contexts. We inevitably fall into the habit of making assumptions about what we are looking at and we look for positive reinforcement of we know. Those assumptions limit the scope of our understanding about what is actually happening.

The best advice I received was to take an anthropological approach and keep asking ‘why?’(always a useful starting question): Why does it work like that? Why is that happening? Why is that not happening? What are the reasons behind this? What are the interests of those involved? Who stands to lose out from this happening/not happening?

When I forget to ask ‘why?’, Somalia becomes much more straight-forward, easier to understand. That is the warning sign that I am viewing things simplistically, because the situation is complex and it is challenging to know what is really happening. The simplistic interpretation usually misses the point.

3. Al Shabaab may not be ‘The Enemy’

Al Shabaab is often presented as the primary driver of conflict in Somalia but the picture is more complex than this binary description: there isn’t a ‘good’ side and a ‘bad side’ (see the previous point on the dangers of over-simplifying).

Firstly, there are multiple conflicts, not just one and those conflicts are multi-layered. Social conflict and marginalisation is expressed through conflict between clans. There is a high degree of political conflict across the whole country at various different levels, including inter-state (e.g. Somalia vs Somaliland, depending whether you accept Somaliland as a separate state), intra-state (e.g. Jubaland vs Federal Government), and localised conflict.

Secondly, there are many conflict actors involved, including criminal interests – it’s not just the Federal Government, Federal Member States and Al Shabaab. And conflict is business, e.g. for the proliferation of private security providers in Somalia. Some of those conflict actors have an active interest in perpetuating the conflict because it provides work and resources.

And thirdly, referring to Al Shabaab as ‘The Enemy’ also makes the flawed assumption that the group is a single homogenous entity. There are different factions, with different attitudes and intentions to deliver their aims.

So, why do people focus on Al Shabaab? They are a major and active conflict actor. But there may be other reasons. Maintaining the focus on Al Shabaab as ‘The Enemy’ is useful for the Federal Government to justify enhanced and flexible security, and the removal of the sanction regime. The international community endorses this presentation of the conflict through its focus on Al Shabaab as the driver of instability in Somalia, rather than using a broader perspective of the various Somalia conflicts. This presents a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of the conflicts in Somalia.

4. It’s the resource, stupid

Securing and controlling resource is critical for power – this is true everywhere, not just in Somalia. The priorities for the FGS have been for some time: 1) retaining power, and; 2) securing debt relief under the Heavily Indebted Poor Country Initiative. Holding power provides the primary position to acquire and control resources; the delayed parliamentary and presidential elections mean a longer stint in this position for the current incumbents, at least most of them. Securing HIPC debt relief was widely considered a triumph for the existing administration as it opens the scope for new international lending to Somalia, which also presents new challenges for accountability.

And conflict (within acceptable limits, as noted above) means money – money for those fighting (AMISOM and Somali security forces), control of sources of money (ports and transit routes). As elsewhere in the Horn of Africa, the instability allows leaders to operate a business model, securing funds for their ‘political budgets’, to rent the provisional allegiances of army officers, militia commanders, tribal chiefs and party officials at the going rate. No-one has the monopoly on violence in Somalia. There is instead a marketplace for this, as other commodities.

Resources drive decisions in the international community too. For many of the troop and police contributing countries, the income generated by involvement in the AMISOM brings welcome revenue – note the reaction from Uganda and Burundi when asked to reduce their troops numbers in AMISOM.

Understanding the resource implications of the current systems and consequences caused by any changes is critical to understanding what is happening and why.

5. We are all protagonists

The international community has its interests in and is, therefore, a protagonist in the Somalia conflicts – overtly in the form of AMISOM, and less overtly in the form of the political, diplomatic and programme delivery. Although striving to Do No Harm, any intervention, or non-intervention, in a conflict necessarily means that the interests are affected, which influences the conflict dynamics.

AMISOM provides the AU with a high-profile mission that demonstrates the value of a multi-lateral African peace-keeping operational capability, funded externally. As well as the resource generated, the deployment of AU troops in Somalia means that they are not at home, perhaps posing a threat to their home governments. Somalia also hosts a high-profile UN mission where staff on lucrative contracts can demonstrate their field credentials, allowing a good move into their next role or promotion. There are incentives for a HIPC deal in the international community too – for the World Bank and IMF, Somalia would become a client again and a new market for loans; for donors they can demonstrate that they are a friend to Somalia by supporting the deal. And donors have other interests, including continuing disputes from elsewhere with proxies and striving to demonstrate the success of the policies and programmes. As we have seen elsewhere, donor funds can have a negative impacts on the country they are focused on.

It is hard to find a genuinely neutral party in Somalia and all of these dynamics have an impact on the conflicts in Somalia.

6. Time to talk

In Somalia, as elsewhere, military solutions are very unlikely to be successful on their own. Political efforts are currently mostly focused on encouraging the FGS to agree the election model and commit to timing. But, given power and influence has been captured by various Somali elites, this is unlikely to be representative. It is not in the interests of those elites to consolidate peace and deliver good governance because they would need to surrender some of their power and control of resources. It is likely to be a long time before a more representative form of government is in place.

Other approaches to end the conflicts have focused on encouraging Al Shabaab defections and de-radicalisation centres seek to undermine Al Shabaab through incentivising additional disengagements. Encouraging defections could be useful element of as part of a comprehensive strategy, but it’s not clear that is in place. And there is a risk that defections leave only those steadfastly opposed to a negotiated solution to the conflicts in Al Shabaab.

Like others, I believe that a peace deal with Al Shabaab and other armed groups (ASWJ) and a political settlement are needed to agree an end to the conflicts. The prospects for that look limited, because those who currently hold the power would hold less if that were to happen. Is Somalia stuck?

Copyright protected, please do not copy.