“Conflict”: What’s in a name?

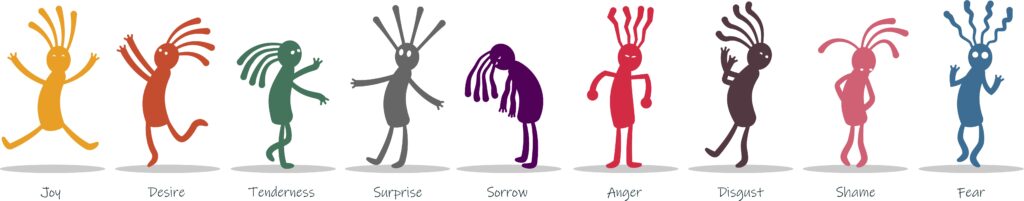

How do you know when you are in conflict? What is it about that situation, dynamic or conversation that makes it feel like you’re suddenly in a difficult conversation?

Is it your heart racing, blood pumping, colour rising to your cheeks and a general sense of unease? For many of us, conflict can be a stressful, threatening experience.

But we may be ‘in conflict’ more than we think.

Conflicting ideas = exchanging ideas

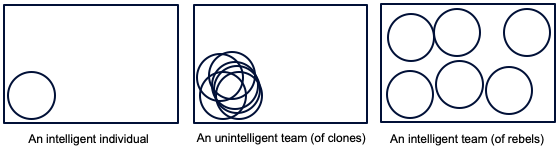

A conflict is actually any time in a conversation with someone when there is a difference of views, opinions, perspective. When we are expressing differing views, opinions or perspectives, we share a something that conflicts with those of the other person. Our ideas conflict with each other. Our views are in conflict. Our perspectives conflict.

This can be a good thing, because that exchange of view, opinions, perspective makes conversation and life interesting. Contrasting ideas can spark creativity. We only have to consider the alternative to see that contrasting ideas are a positive. What would the alternative be? Stagnation. Or not speaking up. That doesn’t sound great.

Positive conflict

So, if many conversations involve an element of difference, why don’t we see that as positive conflict? Sometimes we can be keen to emphasise the absence of ‘conflict’ because that word has a negative association. Paradoxically, acknowledging that there are different ideas being shared can make it easier to open up a conversation about those.

Engaging constructively

So, what can we do when we notice that we’re in a disagreement with someone we are speaking to? It’s noticing that opportunity to embrace the differences and engage in a constructive conversation where ideas are shared.

Here are some tips for that moment when we notice:

- Stay calm: remember this is a chance to exchange ideas.

- Don’t get personal: using language that attacks the other person themselves is more likely to close down the space for a discussion; instead focus on the views, opinions and perspectives.

- Acknowledge the difference: ‘How interesting – it sounds like we’re seeing this differently.’

- Explore to understand: ‘I’m curious. Could you tell me a bit more about what’s led you to that perspective?’

- Share our voice: ‘Shall I say something about why I see this differently?’

You can connect with Pip here for a conversation about conflict.