For many of us, conflict at work is a ‘bad thing’, whether it’s an overt dispute or just the tensions bubbling away under the surface. It’s stressful, distracting and disruptive. And the effects are usually felt by many more people than just those directly involved.

It’s common for our initial reaction to conflict to be to avoid it, or to fight back, to placate or to see if there’s a compromise where everyone gets something so that that issues are less pressing – the classic Conflict Styles described by Thomas and Kilmann.

But what could we do differently – and what might we be missing about the conflict, disputes, tensions that could help us to engage more constructively?

Conflict isn’t necessarily a bad thing

Before we continue, I’d like to pause for a moment.

I’d like to invite you to imagine your workplace. What if there were no conflict in your team? What would that look like?

The dynamic is peaceful. No arguments. No disagreements. Everyone’s personal style is aligned. No clashes. No opposing views.

No differences of opinion, views or perspectives.

Peace….. Or, perhaps, stagnation.

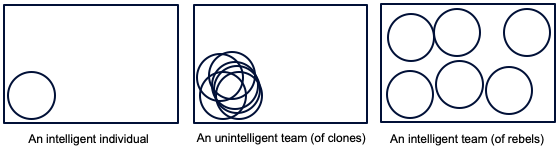

Is that really what we want? Or, is that more like Matthew Syed’s unintelligent team of clones – who all think alike?

Without differing views and perspectives, i.e. without views and perspectives that conflict with each other, we end up with group think. This matters because cognitive diversity strengthens business.

We want disagreement. But we want constructive disagreement. It’s important to be able to share opposing, conflicting views, without erupting into harmful conflict.

If we can see the issues from the other side of the table, then we are a lot more likely to find a way to resolve them

Mediators talk about the iceberg – a party’s position statement is at the top. That’s the bit that you see and hear. It’s what they are saying. Underneath the water, lies their interests, needs, wants. Those explain why they are saying whatever they are saying.

If you focus only on the part of the iceberg that you see, then you are very likely to get stuck. Often those position statements are in opposition to each other. By seeking to understand why the parties need, want, those positions – it gives you more information that is relevant to reaching an agreement.

Mediators also talk about the orange. You may have already heard this because it is a scenario used in mediation training, as well as negotiation training. For those who haven’t, there are two kids fighting over the last orange in the fruit bowl. The parent comes in a decides enough is enough – they split the orange and give each child half. Seems fair, right? One child takes their half into the sitting room, peels it and eats it, throwing the peel away. The other takes their half into the kitchen, peels it and uses the peel for the cake they are making, throwing away the pulp.

What could the parent have done differently? They could have asked why each child wanted the orange. There was a missed opportunity for each child to get 100% of what they wanted.

Developing an understanding of why people in conflict are taking their positions gives you a chance to find a win-win agreement at the end.

Empowering people to find their own solutions is likely to result in longer lasting agreements

When I worked in Somalia, one significant recurrent risk was that the interests of the donors would affect the internal political agreements between different Somali political factions. The sustainability of any agreements reached depended more on the relationships between Somali stakeholders. They were the main actors in the conflict.

A mediator creates the space for discussion, manages the process and listens out for the issues that really matter. They don’t ‘own’ the dispute, nor are they responsible for reaching an agreement. The parties are responsible.

And agreements tend to stick when they have been determined by those directly affected by the conflict.

By

By