Uncomfortable conversations: Love them or hate them?

Who relishes a conversation that feels uncomfortable? Alesha Dixon commented in an interview earlier this year – “I love an uncomfortable conversation. I really do. Because I’m not afraid to learn and to be wrong.” Her comment has really stayed with me. It’s unusual to hear someone talking about difficult discussions in such a positive way.

How do you feel when you’re out of your comfort zone?

It’s not uncommon to feel threatened – as though you’re under attack. If you feel yourself going into flight-fight mode, you wouldn’t be alone. Dan Goleman referred to the “amygdala hijack” in Emotional Intelligence: Why It can Matter More than IQ. That hijack often doesn’t bring out the best in anyone. Steve Peters has described the brain’s reaction to the hijack as a chimp.

It’s a threat

When we perceive specific threats in a social situation, it affects our ability to interact productively. Commonly these are threats to our social standing: having our competence undermined, feeling as though we’re being micro-managed; believing a situation to be unfair. Acknowledging the stressors that trigger our threat responses is a good way to ensure that the confrontation doesn’t get the better of you.

“You’re wrong!”

‘Being wrong’ is a very emotionally loaded phrase. It can get in the way of listening to other perspectives because it’s a rare person who is able to keep practising active listening, when they feel like they are under attack.

It can be scary to admit that you might be getting something wrong – or that you just don’t know about something. If you’re trying to do that in the middle of a conflict, then that’s really tricky.

But it’s important. You may be missing out on an opportunity. Those emotions may get in the way of hearing a different perspective – really hearing it, without that sense of threat.

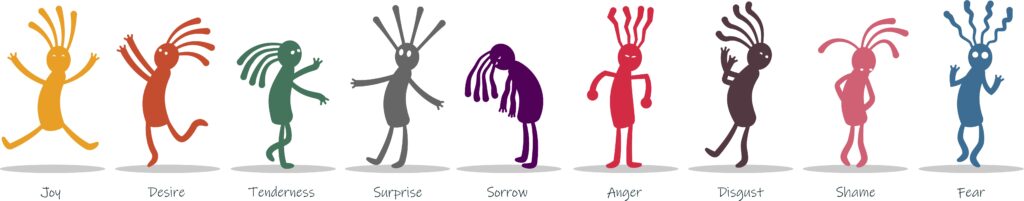

Managing your emotions

Thankfully there’s a lot of advice around about managing that emotional response during difficult conversations. Much focuses on getting your breathing under control – whether as part of mediation, or just taking some deep breaths.

There’s also a classic technique of ‘distanced self-talk’ – as demonstrated by Marcus Aurelius. There’s a shift from thinking ”why am I feeling so upset?”, which is considered immersed self-talk, to a distanced self-talk question, eg “why is Joe feeling so upset?” (if your name is Joe).

Sometimes, getting some support from someone outside the situation can make a difference to how those discussions go. If you’d like some support to manage difficult conversations, get in touch and I might be able to help.